Read: Chapter One Chapter Two Chapter Three Chapter Four

My first targeted chemotherapy drug, Crizotinib, arrived in a plain brown box, held out by the FedEx man as if it was just another Amazon book or Etsy bauble. Inside the box was a thick Ziploc bag with a yellow label reading “CHEMOTHERAPY DRUG. DISPOSE OF AS A BIOHAZARD,” and inside that was a chunky white pill bottle. I lifted the bag gingerly, feeling myself deflate as I looked at the biohazard sign on the label. I, who ate organic vegetables and bought paraben-free soap—I, who filtered my water and had never smoked—was now going to have to put this poison into my body.

Not that there’s ever a good time to get a Stage IV lung cancer diagnosis, but this timing was particularly bad. It was September: we were about to start renovating an apartment and moving house. Perhaps more importantly, our son N was applying to high school, which in New York City is a bit like competing on Jeopardy while also training for the Olympics.

As I turned the pill bottle over in my hands, I thought of N: my once-chubby toddler, now morphed into a stick-thin young man with body odor and chin hair. Before my cancer diagnosis, he’d been the primary cause of worry in our family. Growing up, he’d been a sweet, quirky child, with a sensory sensitivity that made certain sounds and sensations unbearable to him. Fire alarms and shoe stores terrified him; a bicycle might as well have been a torture rack. We often had no idea what would trigger his panic.

A child’s developmental delays can challenge a parent’s love. I’d had plenty of moments I wasn’t proud of, like when I forced N to go down a spiral slide on my lap, only to fall on top of him and break his toe. I’d waved away his loud protests at the top of that slide because we were with another mom and son, and I wanted N to be ‘normal’ so badly that it hurt. I should have listened to him instead of ignoring his very clear signals. Mostly, though, I loved him fiercely and protectively. The idea of leaving him and his sister motherless made me feel sick to my core.

“Well, this is exciting,” I said to my husband, D, after taking the first dose of Crizotinib that evening. “It feels as if I should blow up, or melt, or something.” For emphasis I spread my fingers wide, making an exploding sound. In fact, twenty minutes later I was crouched over the toilet, violently throwing up. My oncologist, Dr. R, had wanted me to see if I could tolerate the first dose without anti-nausea medication, and here was our answer. I had loved Dr. R when we met with him, but at that moment, I hated him a little bit.

Ondansetron, a strong anti-emetic, became my best friend after that. I took it a half-hour before each dose of Crizotinib, and it reduced the vomiting to mild queasiness. Within days, I could feel my energy lift, bringing my mood up along with it. The Crizotinib must be working! It was showing that cancer the door!

But then, during a yoga class later in the week, my heart started beating like a jungle drum during savasana, the final rest.

Over the next couple of days, palpitations came and went. When I Googled “Crizotinib heart palpitations,” I saw that an interaction between Crizotinib and Zoloft could lead to “adverse cardiac events.” Hm. I took Zoloft for depression. Why had no one warned me about this?

It was all so new, and worrying. What to do? On Sunday night, I called the on-call physician at Memorial Sloan-Kettering. “I hate to tell you to go to the Emergency Room, but I’ll sleep better knowing that you did,” he said. And so, armed with this imperative to save an unknown doctor’s sleep, I gathered up a few items—laptop, iPad, a snack—and made my way outside.

I was walking uphill on 116th Street when something stopped me: the moon wasn’t its usual self. Instead, hanging in the sky just above the Columbia campus trees was a shining white scythe cradling a glowing orange ball.

It took a moment before I realized what this was. I’d heard on the radio that morning about the blood supermoon eclipse, a phenomenon that happens only every few decades, when a supermoon (the moon at its perigee, the point closest to Earth) combines with a near-total eclipse. The eclipse sends beams from the sunset around the Earth’s shadow, bathing the moon in rusty hues.

I stood there, humbled by the moon’s ability to be transformed, by light and motion, into this apricot fireball. N had wanted to stay up to see it, and I’d told him there was no point, that the forecast was too cloudy. And sure enough, as I stood there—and before I had the presence of mind to whip out my camera—a thick bank of cloud rolled over and obscured the whole thing. It was over in a moment. But I’d seen it!

I’ve often marveled that opposing forces can occupy the same space. Beauty and ravage, hope and despair, love and grief. Now, as I was on my way to a cancer hospital, this blood moon had shown up in all its fiery splendor. I felt giddy, and guilty that N had missed it.

Unlike the thoracic clinic at Memorial Sloan Kettering, which is surprisingly jaunty, the Urgent Care was as soul-deadening as any other E.R. Lights flickered; the staff seemed zombie-like. An aloof nurse stuck EKG pads all over my torso, and as she drew my blood and fitted an IV, I tried to imagine I was somewhere—anywhere—else.

After she left, I texted D. IV just fitted. Prob here a while.

Ouch, he texted back. High school interview tomorrow morning, remember?

Shit, I’d completely forgotten. Reschedule? I typed.

Prob too hard. Grin and bear it? Plus, N psyched.

I sighed, finger hovering over my phone. Ok.

Forty minutes later, I was weeping into a bleached white sheet. I couldn’t help it: I was just so miserable and lonely. It was so unfair that I had to sit there, under the beeping machinery, while my friends were all tucked up in their beds. To cap it all, in a few hours I’d have to pull myself together and sit through a fucking high school interview.

As I cried, nurses passed back and forth in front of the drawn curtain, and the man in the neighboring bay sighed. I couldn’t stop. It was only the third time I’d cried since getting my diagnosis, and as the tears rolled down, I thought it was probably good that I was letting out my feelings. But after ten minutes, I only felt more dismal.

Dr. K arrived while I was still oozing tears. He was in his forties and sharp-featured, with sleek, well-coiffed hair. My EKG was normal, he said. After a moment, gently but with an edge, he asked, “If you don’t mind—the tearfulness, what’s that about?” If I’d had more presence of mind, perhaps I would have said, “I got a Stage IV cancer diagnosis five weeks ago—how would you be feeling, asshole?” As it was, I burbled something about having been healthy all my life until now. As I spoke, I could almost see his notes—“patient very emotional.” But his face remained impassive as he told me they’d keep me overnight to monitor my heart.

How do you monitor an aching heart? When N was a young child, we’d spent countless hours with doctors and therapists, blindly trusting anyone who claimed expertise. We’d invested in treatments ranging from Omega-3 capsules to compression vests, and we’d hoped and despaired. Then in middle school, without warning, our son suddenly blossomed into a confident, capable young man. There were still quirks, for sure: he couldn’t tie laces, and only ate spinach if he could have milk to wash it down. But for the most part, he was ‘normal.’

Dr. K arrived in the morning with good news: not a single palpitation all night. That ruled out the possibility of a drug interaction. The arrhythmia had likely been caused by stress, he said, or by the Prednisone I’d been given to deal with inflammation. I was free to go.

Out on the street, the light was bright and hard, but the city looked wonderful. Everything gleamed: even pigeons and hot dog stands seemed to have been spiffed up, as if for a movie shoot. Illusory as it might be, it was thrilling to have the sense of being a regular citizen again, walking down the street with no tubes attached to me.

A couple of hours later, D and N and I were running up and down stairs of an elite private school, following an eleventh grader named Heather. Bright and peppy, Heather bounded up and down with the eagerness of a Yorkshire terrier while I dragged behind, trying to smile because I was sure she would be reporting back on us.

Finally, we sat in the office of the Admissions Director, putting on our best faces as she tried to sell us on the idea that the school was diverse and modest (which I doubted, given that one of Donald Trump’s sons had gone there). She talked for a really long time, and I struggled to hide my fatigue. With the make-up I’d plastered on, I felt like a drag-queen version of myself.

Truth was, it was a beautiful school. No doubt, kids who went there would be on a fast track to becoming Masters of the Universe. But our application was more or less an exercise in futility, since—absent a humungous scholarship—we couldn’t afford to send our son there. He was not among the privileged wealthy, just as I was no longer among the privileged healthy.

N was a trouper. He had dressed in his only blazer, which I saw now was getting too short in the sleeves. He’d taken in the tour of the school with bright eyes, and I loved his open and positive spirit.

I wished he’d been with me the previous night on 116th Street. You didn’t need to be rich, healthy or even human to see the blood supermoon—she was nothing if not democratic. She shone alike on Wall Street bankers and Himalayan yaks, on cancer patients and hot dog vendors, painted bronze like Athena going to war. She was tethered to this crazy planet and yet detached from it, untainted, a reminder that wonder could still exist.

I’ve always known that lemon juice was a good liver cleanser, and for a while I was in the habit of drinking lemon juice-spiked water first thing in the morning. But then it got a bit boring, and I fell out of the routine. Until now! I recently discovered a way of making lemon water delicious, fun and extra healthy. It does take a bit of effort (you have to be prepared to use and wash a blender), but isn’t that true of most worthwhile things?

I’ve always known that lemon juice was a good liver cleanser, and for a while I was in the habit of drinking lemon juice-spiked water first thing in the morning. But then it got a bit boring, and I fell out of the routine. Until now! I recently discovered a way of making lemon water delicious, fun and extra healthy. It does take a bit of effort (you have to be prepared to use and wash a blender), but isn’t that true of most worthwhile things?

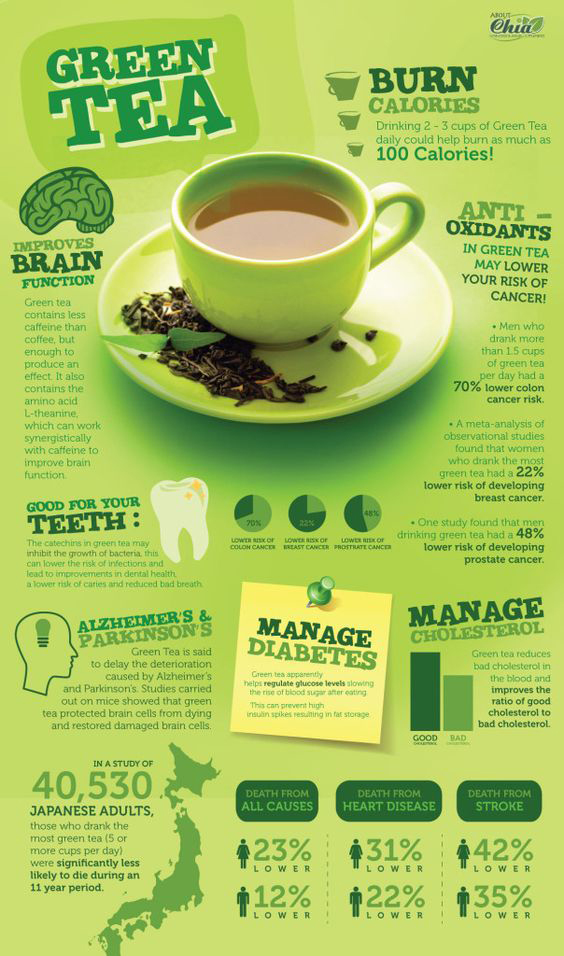

Servan-Schreiber strongly recommends green tea as a natural cancer-fighting force, and as a result I’ve been drinking it ever since. Initially I didn’t much like the taste, but now it has the familiarity of a good old friend, and hardly a day goes by without me drinking a cup or two or three—in fact, I’m drinking one as I type this.

Servan-Schreiber strongly recommends green tea as a natural cancer-fighting force, and as a result I’ve been drinking it ever since. Initially I didn’t much like the taste, but now it has the familiarity of a good old friend, and hardly a day goes by without me drinking a cup or two or three—in fact, I’m drinking one as I type this. A quick survey of medical sites shows that they’re not too impressed by the overall evidence. “There is no real evidence that green tea can help with cancer,” says Cancer Research U.K., which goes on to write, “the research so far is conflicting.” Memorial Sloan Kettering’s Integrative Medicine site says that green tea’s cancer preventive effects in humans “is not conclusive,” and that “human studies are needed.” (For the record, that’s different language from the site’s boilerplate dismissal of other so-called nutraceuticals, which reads, “there is no evidence to support its use for cancer treatment.”)

A quick survey of medical sites shows that they’re not too impressed by the overall evidence. “There is no real evidence that green tea can help with cancer,” says Cancer Research U.K., which goes on to write, “the research so far is conflicting.” Memorial Sloan Kettering’s Integrative Medicine site says that green tea’s cancer preventive effects in humans “is not conclusive,” and that “human studies are needed.” (For the record, that’s different language from the site’s boilerplate dismissal of other so-called nutraceuticals, which reads, “there is no evidence to support its use for cancer treatment.”)